Sake Aroma and Flavour

If you only drink sake once in a while, it can be difficult to find words to describe the aroma and taste of a particular sake and how it differs from another. Compared with wine, the differences within a category are much more subtle, the aromas are restrained and the taste comparatively light.

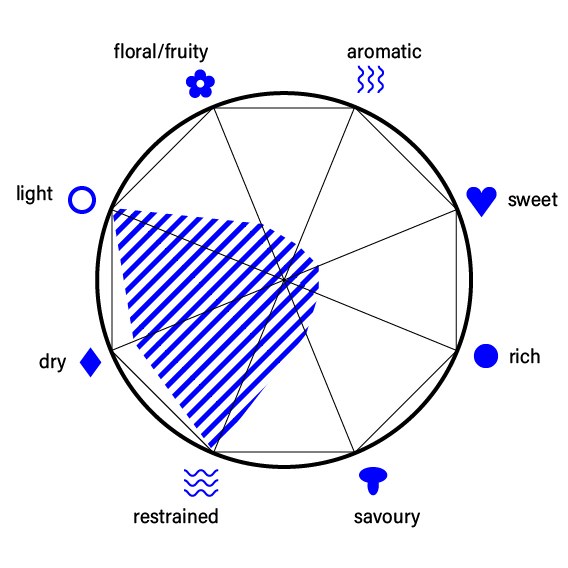

The aroma wheel below (click to enlarge) contains some common descriptors for the flavours and aromas that can be found in sake, plus a few more to describe the mouthfeel and texture.

You can use this as a guide when tasting sake. But keep in mind that taste and smell are very personal — feel free to use whatever words or associations spring into your mind!

In general, many sakes have a fairly mild taste and relatively restrained aromas compared to wine or beer. This is especially true for premium ginjo and daiginjo (made from very highly polished rice), where the aim is to achieve a light and elegant profile.

Acidity, too, is comparatively low. Even sake that is considered ‘high-acid’, such as sake brewed with the yamahai or kimoto methods, has an acidity that is far below that of most wines. A sake with high acidity doesn’t necessarily taste ‘sour’, but will make your mouth water, which can be felt on the sides of your tongue.

Sweetness can vary between styles, although only a few specialty sakes are lusciously sweet. With sake, as with other drinks, the opposite of ‘sweet’ is not ‘sour’ but ‘dry’, meaning the absence of sweetness. A sake can be both very sweet and have a high acidity at the same time. Most sake will appear medium-dry, i.e. with just a hint of sweetness.

Umami, the savory ‘fifth taste’, is unique to sake and is one reason why sake pairs wonderfully with just about any food. Umami is present to some degree in almost all sake but is most prominent in junmai and regular sake (futsushu).

Umami is naturally present in many foods like tomatoes, mushrooms cured meats, cheese, soy sauce. MSG (monosodium glutamate) is pure umami seasoning. Sake, especially if made with less-polished grains, contains many of the same amino acids that are responsible for umami taste.

Styles

Roughly, sake can be divided into four groups:

Light and clear, “refreshing” (mostly honjozo)

aromatic, floral/fruity (ginjo or daiginjo)

full-bodied, rich and round (usually a junmai)

aged sake (koshu)

The overall impression not only depends on taste and smell but also on mouthfeel, aftertaste and the perceived sweetness or dryness. Therefore, these categories don’t align 100% with the designated categories like junmai, ginjo, etc.

Aromatic & Fruity: Ginjo

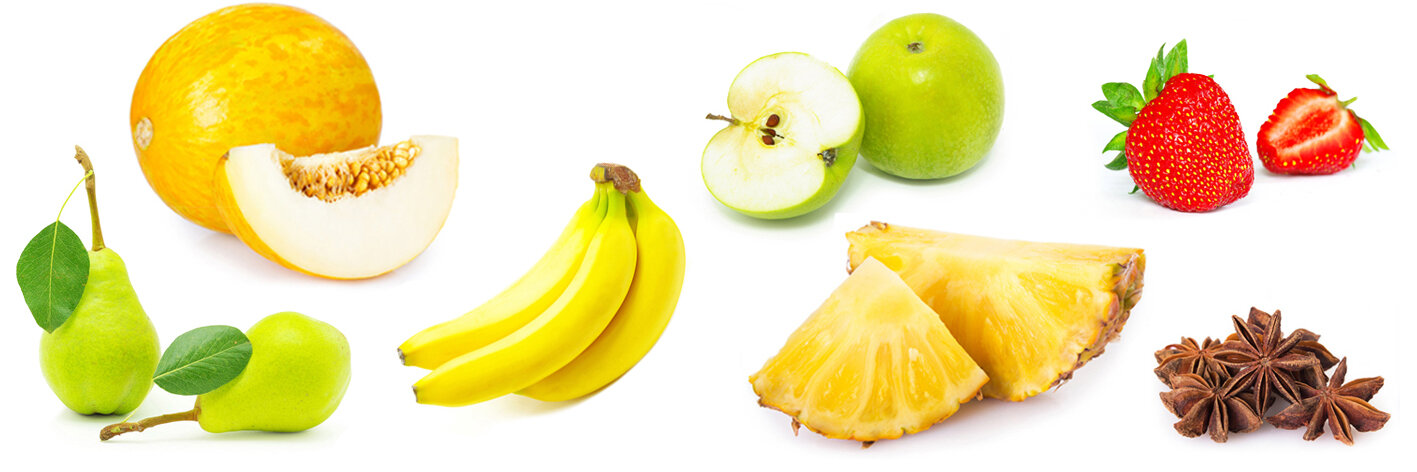

tropical fruits, banana, pineapple, melon, lychee, green apple, pear, bubblegum, aniseed, white flowers

The advance in milling technology was a big game-changer for the sake industry because it suddenly gave sake a new profile. The highly milled rice contributes almost no flavour or aroma of its own, so the yeast can play the main role. A slow fermentation at low temperatures allows the development of aromatic esters.

Specially developed highly aromatic sake yeasts produce a typical aroma of tropical fruits like banana, pineapple or melon, and green apple or pear, and even bubblegum and aniseed while developing only little acidity.

This aroma profile is called ginjo-aroma (ginjo-ka), and with a bit of experience you will be able to pick out a ginjo or daiginjo by smell alone.

There are many excellent ginjo/daiginjo sakes out there, and its a very popular style that is easy to like, even when you are new to sake. Dassai is one of the more famous ‘premium’ brands. Try the Dassai 45 or 39 (made from rice that has been polished to 45 or 39% of its original volume). It is produced in comparatively large volumes and should be easily available.

If you’re a fan of aromatic wines like Riesling or floral and light italian whites (Pinot Grigio, etc), Pinot Blanc/Weißburgunder, this is where you’ll want to start with sake. Same if you prefer your beer as a shandy/radler or a light Belgian wit.

Rich & Round

ripe banana, banana bread, fresh nuts, rice bran, rice porridge, herbs, acidity, umami, full body

Junmai sake is produced with less-polished rice and therefore has more umami and rice-derived aromas. The amount of koji can also play a role, as amino acids will make the sake seem feel more ‘round’ and creamy and give more body to the sake.

The fruit aromas will be less fresh and ‘green’ but more ripe and ‘yellow’ (think very ripe banana or banana bread). The bouquet can be quite complex with a mix of grainy and herbal aromas, too (like rice porridge, rice bran, cereal, but also fresh mushroom).

If the sake is furthermore undiluted (genshu [原酒]) and unpasteurised (nama-zake [生酒]) this, too, will add to its complexity and richness. The use of traditional brewing techniques like Yamahai [山廃]or Kimoto [生酛] (more on these in another article) also results in a sake with funkiness, complexity and umami.

This one is for the lovers of full-bodied Chardonnay and smooth reds. But don’t feel left out if you prefer natural and/or orange wines; this style can offer some ‘funky’ aromas as well! If you like ales and unfiltered beer more than plain pilsener/lager, this should also be an interesting style of sake for you. Last but not least, the rich character might also appeal to lovers of rum and bourbon.

Banana, fig, nuts and grains are typical notes you can get from a junmai sake.

Light and Clear

clean, light, dry, restrained, refreshing, rice bran, lemon, milk, mineral

Honjozo will often be made in this style. The added alcohol gives it an overall lighter and dryer impression. The aromas are restrained because of the relatively higher milling rate and the use of a non- or only lightly aromatic yeast.

For this style, mouthfeel is as important as taste and smell. The overall impression should be clean and refreshing, which is why this style is popular with fish such as sashimi; it can work like a palate cleanser without being overpowering.

Niigata Prefecture on the western coast of Japan is especially known for producing dry and clean-tasting sake. Kubota Hyakuju is a good example of this style that is easily available in many markets.

If you like your beer ice cold, light and refreshing, this will be a sake for you. As this style is quite dry, it will also be interesting to try if you usually prefer clear, vodka- or gin- based drinks.

Light and clear sake is a good match with fresh seafood and works as a palate cleanser.

Aged Sake

honey, caramel, dried fruits, roasted nuts, soy sauce, ham, spices, sweetness, umami

Aged sake is a category all of its own. Sake is generally meant to be drunk fresh; preferably within one year after release. But some breweries produce sake specifically for ageing.

The Japanese name for aged sake is koshu [古酒]. The sake is stored in tanks, or ceramic jars at the brewery for a few years before sale. Some breweries store their sake cool, while others let it rest at room temperature. Often this sake will have a pronounced sweetness, which fades away with age, just like in dessert wines.

As sake ages, the colour changes from clear to golden, then amber and eventually brown.

As it gets older, the sake changes colour: first to a bright gold, then tawny and eventually a dark brown. The taste changes too: sake aged for 3–5 years will taste of honey, caramel and nuts. With further age, koshu can even develop notes reminiscent of soy sauce, roasted nuts and ham.

Daruma Masamune (Shiraki Brewery) is a famous brand of aged sake. They are available from a range of importers outside of Japan and offer a tasting set with three small bottles that gives a good introduction to aged sake. Try it like a desert wine with vanilla ice cream or chocolate, or with cheese!

If you like sherry and (aged) sweet dessert wines or vintage port, this will be right up your alley. Also whisky and cognac drinkers might find aged sake interesting. Chinese Shaoxing wine can have similar characteristics as well.

The Bad & The Ugly

rancid, musty, moldy, vinegar, damp cardboard, burnt hair

Of course, also sake can go bad. The most likely culprit in that case is bad storage, i.e. light or heat. What does it taste like? Well, for most part, it’s easy to spot a faulty sake, even before the first sip. If it smells rancid or musty it’s obviously past its due date. Light damage leaves a characteristic smell similar to burnt hair. If you pick up something like wet cardboard, that’s also a bad sign.

Unpasteurised sake is, naturally, especially in danger of changing character due to improper storage. It should always be kept cold (ideally at 4ºC or less) to avoid that any enzymes or other live elements in the sake become active and is best enjoyed soon after its release. Unpasteurised sake can develop a sweet, slightly musty smell that some people compare to freshly baked brownies that have been in the oven just a little too long. In small doses, this is not necessarily an unpleasant aroma, but it’s still fault and can overpower the other aromas in the sake.

Sake that has not been store properly can develop off-flavours and aromas. Cloudiness, floating spots (photo) are also an indication of a faulty sake.

Furthermore, there are some aromas that are not faults per se, but are unwanted in premium sake. Ginjo sake can sometimes have an aroma similar to nail polish remover (ethyl acetate) which can become quite unpleasant. And the same compounds that give you green aromas of freshly cut grass or green apple can become too strong and take on a much less attractive medicinal note. Bitterness is usually not an issue with sake, but would also be considered unwanted if present.

For a long time, lactic notes of any kind were also considered unwanted, especially at national sake competitions. Nowadays, attitudes have become more relaxed and many people will find a little bit of a fresh, yoghurt-like aroma quite pleasant if it fits the character of the sake.

Sake brewers and professionals use a special standardised cup to evaluate clarity, colour, aroma and flavour.